Grist Mills in Stillwater and Fredon: A Survey (2007)

by Rob Jacoby

I. Introduction

Water-powered mills in rural areas were the catalyst for the industrial revolution in America, and they continued to dominate the economy and character of those places long after industry had become synonymous with fossil fuels and cities. By taking advantage of the kinetic energy of flowing water, the waterwheel was able to efficiently transfer work to machinery for grinding grains, sawing wood, processing wool, and a variety of useful tasks. In New Jersey, hundreds of mills were established on rivers and streams from the colonial period through the nineteenth century, and the watercourses on which they were located often functioned both as motive force and as transportation routes for their finished products.[1] Mills stimulated the growth of agricultural settlements and in turn thrived as the population grew. In Sussex County, New Jersey, gristmills played active roles in the development of the local communities by serving as incubators of commerce and industry. Keen’s Mill in Stillwater, and Hunt’s Mill and Whittingham Mill in neighboring Fredon, are a historically significant group of properties as defined by the National Register’s Criterion A by representing various facets of the Era of Rural Commerce and Industry from 1840 to 1920. These mills are also significant for their demonstration of the theme of Adaptive Engineering, and illustrate the strengths and limitations of waterpower as a reliable energy source.

II. Mill Descriptions

Keen’s Mill is situated near the southern edge of Swartswood Lake along the outflow of Spring Brook, a tributary of the Paulinskill River (Figure 1). The 2½-story mill faces the road that connects the villages of Middleville and Swartswood, following the curve of the lakeshore. At 30 x 50-feet, Keen’s Mill is the smallest of the mills in the present survey. The front elevation rises about 35 feet to the ridgeline of the steeply canted roof, with the rear elevation reaching approximately 51 feet, an elevational difference that is roughly equivalent to the fall of water that operated the mill (Figure 2). The mill was constructed of limestone that likely was quarried from a nearby ledge. Large rectangular blocks form the quoins while smaller stones, many of them irregular in shape, make up the principal segments of the walls. An overhang projects from the peak of the front gable from which a pulley was used to hoist sacks of raw grain into the mill and to unload processed flour onto wagons. Slate shingles cover the roof.

Windows on the gable ends are symmetrically placed and decrease in size with each successive story, while the windows on the long walls are irregularly spaced. Several original windows were replaced in the 1970s, after the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection purchased the mill and property.[2] A large portal on each floor served the loading and unloading of grain and flour. A single entryway at ground level is along the north wall, offset to the northwest corner. Stone archways are visible within the framework of the north and east walls (see Figure 2). The waterwheel and shaft were supported through the arch in the east wall, while the north wall archway was a retrofit for conversion to an interior turbine around 1903. Both archways are presently sealed with limestone blocks.

Waterpower for the mill operation was obtained by damming Swartswood Lake’s outlet at the narrow point of Spring Brook, and directing a high velocity flume of water, via millrace, to the waterwheel. The current dam (Figure 3), the third to be built at this spot, was installed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the 1980s[3], and in the process, eliminated the headrace. Portions of the tailrace are still visible below the mill along Spring Brook.

Hunt’s Mill is located at a sharp drop on Bear Brook, a small tributary of the Pequest River. The mill was constructed of limestone in a style similar to Keen’s Mill, with large rectangular blocks forming the quoins, smaller pieces in-filling the remainder of the walls, a steeply canted roof with slate shingles, and multiple portals below the overhang on the gable end facing the road (Figure 4). Large blocks also form the window lintels and sills. Unlike Keen’s, however, Hunt’s Mill was built with rows of symmetrically placed windows, and a ground floor entrance centered on the front gable. The footprint of Hunt’s Mill is large, about 36 x 65-feet, but its real bulk appears at the rear, where it scales approximately 75 feet from the base of the foundation to the ridgeline (Figure 5).

Situated abreast of the mill is the milldam (at left in Figure 5). Though raising the height of water only an extra three to four feet above its natural fall, this additional drop greatly increased the force of the water on the wheel, and by impounding the stream created a reserve of water during dry seasons and droughts.

The miller’s house, a 2½-story stucco-stone dwelling built circa 1850, sits across the road from the mill. A wood board and batten barn completes the trio of structures at Hunt’s Mill, and is situated along the millpond just upstream from the mill. Although the mill has long been abandoned, the house has continuously been occupied since first constructed.

The Whittingham Mill, squeezed onto a steep slope along a small drainage, appears to overwhelm the landscape with its mass and 70-foot length (Figure 6). Yet, when seen from its upslope gable end, its 26-foot width seems almost diminutive (Figure 7). Constructed of limestone finely cut into random ashlar blocks, the windows display pronounced granite lintels and sills, and are set at standard intervals across the long walls; seven windows on the upper floor, five on the middle, and two on the bottom as the floor length diminishes due to the extreme slope. The dark color of the slate-covered roof matches the shade of the lintels and sills and establishes an aesthetic rhythm that is unusual for a rural mill.

II. Mill Descriptions

The mills in this survey are located on secondary drainages approximately four miles apart, and were part of a wave of second and third generation mill construction in the Kittatinny Valley. The earliest mills in the region were built on the most accessible reaches of the Paulinskill River in the mid- to late-1700s, and later millwrights were forced to build on steeper grades in narrower stream valleys. Steep gradients have the advantage of providing greater water velocity and thus greater force, but one must also deal with the problem of additional support for the mill structure. The structure and materials of the three mills, therefore, can be seen as responses not simply to traditional forms of mill construction but also to the geology and topography of the eastern slope of the Appalachian Mountains through the use of locally available limestone and the need for massive multi-storied foundations.

In 1824, George Keen purchased 81 acres at the outlet of Swartswood Lake from John Rhodes for $3200.[4] Included in the property was a small gristmill erected by Rhodes’ father around 1790, which Keen ran until he built the present mill in 1838. Building a new gristmill was a risk because mills were already established in the vicinity, including Theophilus Hunt’s in Middleville, less than a mile away, and Shafer’s Mill in Stillwater, about two miles distant.[5] Still more were located in Marksboro, Fredon, and Blairstown, all within a ten-mile radius. Keen’s good fortune, however, lay in his proximity to Swartswood Lake, which functioned as a huge millpond for his operation. During dry seasons or droughts, streams may run dry and even river flows may become insufficient for profitable operation of a water-powered mill. But at 510 acres, Swartswood Lake regulated flow and protected Keen from all but the worst such seasonal fluctuations.

Keen profited too by the relative efficiency of his new mill. Mill equipment undergoes a tremendous amount of stress, with the constant rotation of the wheel, shafts, gears, pulleys, and stones requiring frequent maintenance and repair. Waterwheels, in particular, suffer in northern latitudes from winter ice damage. Keen was able to parlay his efficient mill and the growing output of the farms around the village of Swartswood into a commercial enterprise that he and then his son John, maintained until the latter’s death in 1898.

William Vail purchased the mill from Keen’s heirs, and in 1903 replaced the vertical waterwheel with an interior cast-iron turbine, a highly efficient mechanism that was also less vulnerable to ice damage.[6] The costly overhaul was intended to permit the mill to effectively compete with newer mills built specifically for turbine power. But before Vail could financially gain from the new equipment, the milldam collapsed under the pressure of a heavy rain, and Keen’s Mill was effectively abandoned. Keen’s Mill is a significant historic building because of its contribution as a long-running rural commercial enterprise to the growth of the village of Swartswood. Its proximity was a benefit to local farmers by keeping shipping costs low, and in so doing, encouraged growers to expand their cultivated acreage. The mill is also significant as a demonstration of an old structure’s ability to be adaptively re-engineered for new technology without losing its essential structural and architectural character. The decade or so around the turn of the twentieth century was a critical time for small-scale rural industries in their bid to remain competitive against factory-system mills relying on high volume processing and powered by fossil fuels. Had the dam not collapsed, Keen’s Mill might have proven to be efficient and competitive enough on a local scale to stay in business for decades more.

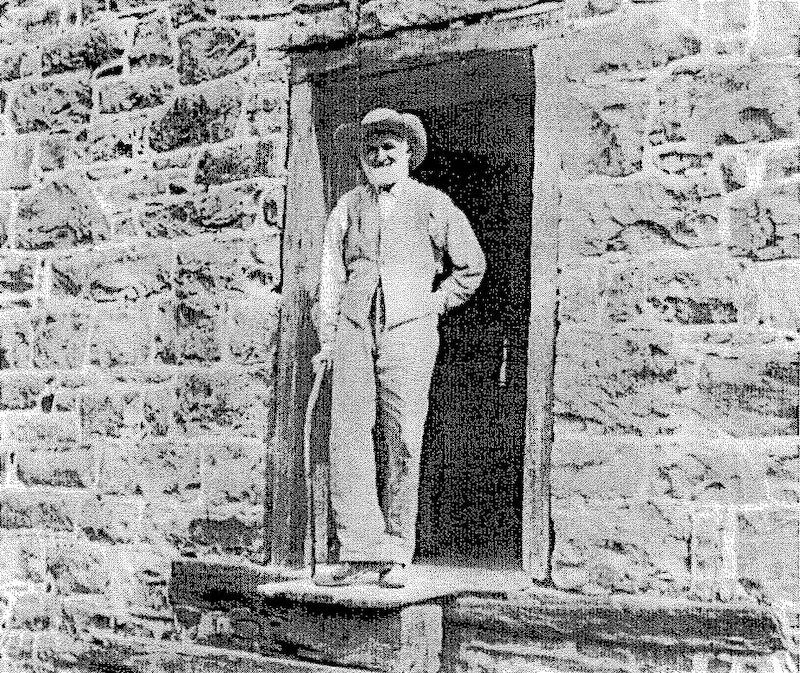

The nearly vertical drop of Bear Brook in Green Township[7] was a natural attraction for milling operations, and in 1780 Ralph Hunt acquired around 325 acres and built the first mill at this location.[8] His estate was divided upon his death in 1821, and his sons, Joseph Hunt and Thomas P. Hunt, acquired the mill property.[9] The present stone mill was erected in 1844-45 by Thomas, who increased the height of the milldam, installed lift-gates to control flow, and oversaw a thriving water-powered industrial hamlet inhabited by the extended Hunt family by mid-century. The 1860 atlas of Sussex County depicts a gristmill, plaster mill, and sawmill at this spot.[10] Other accounts indicate the presence of a fulling and carding mill, a distillery, and a clover mill,[11] although some of these activities may have represented adaptive reuse of the stone mill itself. In contrast to Keen’s Mill, which was on the edge of an expanding village, Hunt’s Mill was located in a landscape of dispersed farmsteads. Control of the mill passed to Thomas’s nephew, Theodore Hunt (Figure 8), and in 1886 he installed an interior turbine as a replacement for the vertical waterwheel. For forty years this turbine powered the mill until failing in 1926, at which point all milling ceased. Hunt’s Mill is significant as a historic building because of its role as a center of rural commerce and industry for 80 years from around 1845 to 1926, because it has retained a great amount of structural integrity from its original form, and because it demonstrated the flexibility of design to be able to adapt to changing technology while retaining its essential water-powered character.

If one mill can be considered significant due to its success, can another be significant despite being a colossal, though interesting, failure? Walton Whittingham purchased farmland in 1900 that included a steep draw and small stream.[12] He built a large gristmill at this location in 1904, so one story goes, to spite the Hunts after a dispute.[13] Despite installing state of the art milling machinery and efficient turbines, it quickly became obvious to Whittingham (and all doubting onlookers) that the water source did not provide sufficient power for the mill.[14] Having invested heavily in its construction, Walton Whittingham erected a steam-powered generator in an effort to keep it running. This proved too costly, and after an attempt to generate electricity for distribution on a local grid, Whittingham abandoned the mill sometime around the First World War.[15] The Whittingham Mill is significant not for its failure but rather for the attempt to harness water power in a sub-optimum rural setting at a time when many rural industries were disappearing or shifting to urban areas. The innovative conversion from water to steam power, while ultimately unsuccessful, was a critical effort in this regard. And finally, its short use-life limited potential alterations in later years, resulting in a mill building that has remained virtually unchanged since its date of construction.

The stone gristmills of Sussex County are a significant collective resource under the terms of the National Register’s Criterion A, because they represent important themes in the history of industry, commerce, and engineering in the Kittatinny Valley. In their dormancy they have become immutable elements of the landscape, older than living memory, and rooted in the character of the region’s people.

(All photos by author)

Footnotes

[1] By 1751 there were already 246 gristmills and 185 sawmills in the province of New Jersey. Peter O. Wacker, “The New Jersey Tax-Ratable List of 1751,” New Jersey History, 107:33 (1989).

[2] Personal communication from Bud Teare, Stillwater resident and mill preservationist.

[3] McCabe, Wayne T. and Kate Gordon, An Album of Postcard Views: Stillwater, New Jersey. (Newton, New Jersey: Historic Preservation Alternatives, Inc, 1998), p. 23.

[4] Sussex County (N.J.) Deeds, Book Z2, Page 453, (April 10, 1824).

[5] Snell, James P., The History of Sussex and Warren Counties, New Jersey, (Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1881) pp. 380-382.

[6] Wright, Kevin. “Keen’s Mill at the Outlet of Swartswood Lake,” interpretive pamphlet distributed by the New Jersey State Park Service, Northern Region, n.d.

[7] The area around Hunt’s Mill was incorporated as Fredon Township in 1904.

[8] Snell, ibid., p. 433.

[9] Sussex County (N.J.) Divisions, Book B, Page 54 (September 24, 1822).

[10] Hopkins, George M., Map of Sussex County, New Jersey (Philadelphia: Carlos Allen 1860).

[11] Dale, Frank. Grist Mills. (Hackettstown, NJ: Minuteman Press, 2001), pp. 1-5.

[12] Sussex County (N.J.) Deeds, Book Q, Page 243 (March 29, 1900).

[13] Personal communication, Bud Teare.

[14] Kaiser, Judith Cummings, A Pictorial Sampler of Historic Fredon. (Iselin, NJ: Press of Impact Printing, 1998), p. T-13.

[15] Personal communication, Myra Snook, Town Historian, Fredon Township, NJ.