Lenapehoking: Land of the Lenape for 12,000 Years

Wherever you set foot in Stillwater Township today, you can be sure that people of the Lenape tribe and their ancestors tread upon that ground for thousands of years before you. Stillwater’s first settlers arrived in New Jersey more than 12,000 years ago.

The Lenape, (pronounced Len-AH’-pay) were called Delaware Indians by the early European settlers because their territory spanned both sides of the Delaware River. The natives called their homeland Lenapehoking and it occupied all of present-day New Jersey, eastern Pennsylvania, south eastern New York State, Staten Island, the western part of Long Island and parts of the state of Delaware.

The Lenape people living in the Sussex County area spoke a dialect call “Munsee” while their tribesmen of southern Jersey spoke “Unami”, both of which are dialects related to the Algonquin language. Their society was democratic and their culture was matriarchal, although labor was divided between the genders. Men did the hunting while women took care of the children and did pottery work, weaving and tended to the farms. Around 1,000 years ago, the First Americans settled into a more agricultural lifestyle, growing corn, beans and squash in villages along the banks of the Delaware River, Paulinskill River and other river basins in the region.

Lenape society was matriarchal. Women owned property and were leaders of the community.

Men were the warriors for the tribe, but women dictated which men would go into battle.

Contact with Europeans

The first European to observe and record the Lenape was Italian explorer Giovanni de Verrazzano whose ship sailed into New York Bay near Sandy Hook in 1524. In one of his letters, Verrazzano writes a glowing description of the people standing along the shore who welcomed his boat with enthusiastic gestures.

“These people are the most beautiful,” he wrote. “They are taller than we are, they are a bronze color, their face is clear-cut….their eyes are black and alert, and their manner is sweet and gentle.” The close encounter was thwarted when a sudden gust of wind from the sea forced the crew to sail on and forgo their landing.

With the exception of this encouraging moment, the Lenape people did not benefit from contact with the Europeans. The foreign countries were competing to claim territory in the “New World” in order to enlarge and enrich their colonial empires around the world. The new immigrants also brought diseases from Europe for which the Native Americans had no immunity. By 1750 the mortality rate among the Lenape was as high as 75%, according to some estimates.

The Lenape attempted to trade and negotiate with the settlers, but the cultural differences were insurmountable. They did not recognize the European concept of private land ownership. They signed treaties and agreements that were fraught with misunderstandings. The first treaty, which the Lenape signed with Thomas Penn, the son of William Penn, was known as “The Walking Purchase” of 1737. The Lenape believed they were tricked out of the homeland which their ancestors had inhabited for 12,000 years and began to move westward in search of land free of European invaders.

Lap-pa-Win-Soe was a Lenape chief and a signer of the “Walking Purchase” or Treaty of 1737 which was signed with Thomas Penn. The first of many unethical treaties between Indians and settlers, the Walking Purchase defrauded the Lenape of most of their land and marked the beginning of two centuries of Indian dislocation.

Thomas Penn, architect of the unethical Treaty of 1737, was the son of Quaker William Penn who was instrumental in bringing farmers from the Palatine to Pennsylvania and even Stillwater.

The First to Face the Onslaught

Often called the “Delaware Indians,” the Lenape people have not entered the consciousness of non-indigenous Americans as strongly as have the names of tribes which made star appearances in Hollywood westerns in earlier days. The Apache, Commanche, Lakota and Iroquois are among the tribal names that have caught the imagination of the general public, thanks to the roles in which they were cast in commercial films. The Lenape, however, played a leading role in the true history of cultural conflict which the Europeans brought onto the mainland of North America. They should be remembered for being the first to undergo experiences which would eventually impact all of the tribes on the continent.

They were the first to see and be seen. Many Lenape people dwelled along the coast of the Atlantic Ocean —the Jersey Shore—and therefore were among the first to spot the white man’s boats and to be spotted by them as well. In 1524 they waved to Giovanni da Verrazzano when his fleet sailed along the Atlantic coastline near Sandy Hook.

The Lenape were also the first among Native Americans to be offered a reservation existence. The Brotherton Reservation, near the town of Indian Mills in New Jersey’s Burlington County was opened in 1758. It was short-lived. Residence required adherence to the Christian beliefs of the reservation founders, which meant abandoning Lenape traditions and spiritual rituals. An even greater push factor was the environment at Brotherton. The Lenape found life on a reservation to be a pitiful alternative to their rich and free existence in the natural world, where they had roamed the Blue Mountains and fished in the many lakes and rivers of the Delaware watershed before “New Jersey” became the official name for their “Lenapehoking.”

Finally, the Lenape were the first indigenous people to leave their homeland in search of a better life, unhampered by the troublesome white settlers whose numbers grew and whose aggression intensified with the justification of the doctrine of “Manifest Destiny.” They began to move westward and after many unsuccessful attempts to find a new home, they settled in Oklahoma and Wisconsin. Others headed north and started communities in Ontario.

The Lenape’s position of “seniority” in the tragic events of Native American history is an ignominious classification which is meaningless to an ancient people of refined culture. It is a point that has significance only from the perspective of the European invaders who were the perpetrators of the events of dislocation and cultural extermination.

Today many people are eager to learn a more accurate history of the indigenous people in North America than was taught in schools in the past. Many publications and documentary films are now available which dispel misconceptions and also introduce ancient indigenous wisdom about the workings of the natural world. At this critical time in the history of the planet, humans can benefit greatly from studying traditional Indian wisdom about the role of humans in an interconnected world, and the concepts of reciprocity, sharing and respect for all living things.

The Lenape People in the New Millennium

Today there are 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States known as “sovereign nations.” The population of Native Americans and Alaskan Natives totals 9.7 million or 2.9 percent of the total U.S. population. This number includes the Lenape people who spread across the continent in the 18th century.

Only several thousand Lenape people live in New Jersey today, including the Ramapough Lunaape (Munsee Delaware) who never left their ancestral homeland in the Ramapo Mountains near Ringwood, New Jersey. As with most Native American tribes, they maintain their traditional values and strive to inculcate the younger generation with a reverence for their culture and for the environment.

The 2010 Federal census documented 25,000 Native Americans living in the state of New Jersey. Today, these residents include members of many different Indian groups—Apache, Commanche, Navajo, Shinnecock and Mohawk—as well as descendants of New Jersey’s original indigenous population.

Prior to the middle of the twentieth century, historical accounts often led readers to assume that the Native Americans had been vanquished into extinction by the civilized white man. Despite the many campaigns launched to exterminate their people, Native Americans have demonstrated extraordinary tenacity and cultural resilience. Although considerably beaten down by the injustice and suffering, they have survived five hundred years of persecution with their culture intact. This is a remarkable feat. Their resilience is the very trait which will equip them to survive and thrive in the face of a daunting future on our planet.

Daniel M. Cobb, Professor of American Studies at the University of North Carolina, suggested the following catchphrase to unhook the myth from misled minds:

“The Native Americans are not a people from our history, but a people with a history; they are not a people of the past, but a people with a past.”

The Indians of the past are very present among us. Their ancient wisdom is alive and could guide us to heal the earth together and to unite as the people of the future.

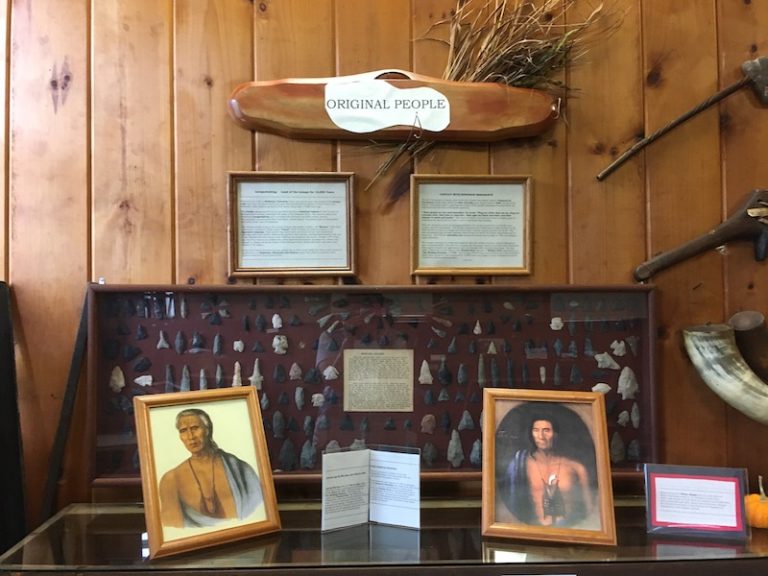

Native American Artifacts in HSST Exhibition

Dr. Edward Cosgrove, lifetime member of HSST, donated a large collection of Native American artifacts, Stillwater photos and vintage postcards to the Society. His donation is a wonderful addition to HSST’s collection and we extend our thanks to Dr. Cosgrove for his generosity.

Following is just a sampling of items in the Cosgrove Collection. We encourage you to visit the Museum this summer during our Sunday openings to see the collection or -email- to arrange an appointment.

Native American Artifacts

The Native American artifacts were found on the property of Mr. Levi T. Serey. Mr Serey, a Middleville farmer in the early-mid 20th Century, was married to May Hill, Dr. Cosgrove’s relative. The farm was located on the current Route 521 in the Keen’s Mill area and is shown on the map below:

The artifacts range from arrowheads and axes to ornamental pieces and pestles.

Ax Head:

Gorget (ornamental piece worn around the neck; had a ceremonial purpose):

Nutter (used to grind nuts in the concave area):

Photo Albums

There are two photo albums in the Cosgrove Collection, both of which belonged to May Hill Serey. The earlier album (before circa 1917/1918) centers around the Lake House, a hotel May’s parents owned in Swartswood. The later album (post circa 1917/1918) centers around the Middleville farm that would later belong to May and Levi Serey. It had a boarding house called Lake Cottage as well as a schoolhouse.

This line crew, shown in Swartswood, laid the first phone lines in the area:

Levi Serey, working the Middleville farm:

Postcards

The postcards in the Cosgrove Collection primarily consist of Stillwater area postcards, though New Jersey at large and other geographic locations are represented. The messages on some of the postcards give us a glimpse into everyday life in our area in the early 20th Century. One postcard promises a secret if the reader looks under the stamp. Of course, the stamp is long gone – and the secret along with it.

Robbins Store:

Swartswood Post Office and General Store:

High Falls House:

Additional Resources

- New Jersey State Museum

- Website of Lenape Lifeways

- Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn by Jean R. Soderland, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

A Nation of Women: Gender and Colonial Encounters Among the Delaware Indians, by Gunlog Fur, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 2009.

- Lenape Indian Cooking with Touching Leaves Woman, Nora Thompson Dean. Second edition prepared by Jim Rementer. © Touching Leave Company, Bartlesville, Oklahoma, 2016.

Materials for children and young people:

The Lenape or Delaware Indians © 1996 by Herbert C. Kraft, Archaeological Research Center, Seton Hall University Museum, South Orange, New Jersey.

People of Twelve Thousand Winters, Trinka Hakes Noble, Sleeping Bear Press, Ann Arbor, 2012.

An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States For Young People, by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, adapted by Jean Mendoza and Debbie Reese, Beacon Press, Boston, 2019.